Recently, a seventy-year-old man stood sobbing outside a police station with a piece of paper that was worth nothing. It was a receipt for a parcel that did not exist, a scam that gulped his hard-earned pension. But the officers could only shake their heads—his money, lost, spent on the secret coffers of the swindlers who were now so rife and sophisticated that the authorities had begun allocating millions to combat them. And this is where the tragedy really starts: the swindles are no longer secretly working criminals working out of the shadows. They are an accepted norm in society, a cancer people just learn to live with.

How did we get here? When did we come to accept the fact that dishonesty is not only present but flourishing? Disinformation has been the template upon which this game of deception has been built. The digital age, when information was laid at our feet, is now a wasteland of lies. Social media each day vomits disinformation masquerading as news, Ponzi schemes masquerading as actual investment plans, and fabricated victim tales intended to pull at emotions and drain bank accounts. And at the core of it is the confused general public, unable to tell truth from fiction. And for the fraudsters? They dwell in this mist of ignorance, feeding off credulity like wolves at a perpetual banquet.

That was the time when con artists walked in dark backstreets, issuing sotto voce promises of easy money. Nowadays, they give seminars, dress in business attire, and hire hotel ballrooms to impart their veneer of respectability. Others become influencers, too, wearing designer watches and luxury cars, their fans living by their words as they sell empty promise. They’ve discovered that people are more likely to part with their cash if they can persuade them that they’re being taken to the top and not robbed. The trench-coated old-school con man has given way to the slick scammer with a PowerPoint presentation.

More horrific is the way individuals have become accustomed to living with this infestation, as with a town accustomed to rats. Companies now include potential fraud in the consideration when they make a transaction. Banks have anti-scam campaigns as if they are part of their customer service routine. Schools educate kids about cyber scams just as they used to teach about stranger danger. Governments spend public money to fight fraud, but only to verify what we already know: fraudsters are here to stay, a crisis that we will have to learn to live with instead of getting rid of.

And do not forget the brazenness of these fraudsters. They take advantage of people’s generosity, making human kindness a liability. Charity scams rob those who want to give. Imposter recruiters offer job opportunities to the desperate. Romance scammers steal life savings from lonely hearts. At the bottom of it all is a gruesome reality: they know more about human nature than we do. They know our hopes, our fears, and our vulnerabilities—and use them without pity.

Worst of all, though, is not even the presence of swindlers but society’s tacit condoning of them. We tease about “being scammed” as if it were a rite of passage. We shame victims for being dumb rather than shaming the deceivers. We swipe over scam alerts, believing that they are for other people, until the day our bank accounts are drained by a message we shouldn’t have tapped. Scammers don’t only take money; they take from us trust, so we are always on guard for anything that asks for faith or charity.

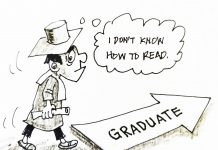

Legislation can be enacted, campaigns can be run, but in essence, it’s a struggle against human ignorance. The remedy isn’t just in regulation, though—it’s in education. We need to teach discernment as a survival skill, like reading and writing. We need to create a culture of veracity instead of spectacle and skepticism instead of ignorance. Most importantly, we must decline to accept fraudsters as the norm. Because the minute we do, we have already lost.