It has become a trend that when oil prices increase, all the rest follow suit like a domino effect, leaving the buying public in shock, hardly able to cope with the soaring cost of living.

But when said oil prices go down, prices of commodities that had gone up with it never return to their original amount anymore.

It can be recalled that in the past weeks and months, oil prices in the country soared high that in some remote gasoline stations, per liter selling of diesel and gasoline almost reached a hundred pesos.

In urban centers like Tacloban, prices reached almost P90 per liter in that same period. That’s relatively high compared to the original, usual prices that ranged from P48 and P52 per liter.

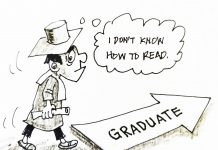

As these developed, prices of almost all commodities including fares likewise increased while the salaries and wages remained the same.

How are the people to cope with these changes financially? When all the prices of basic needs and wants have gotten up, and the salaries remain the same, how can the salary-earning population manage their finances? There is only one solution supposedly—get the oil prices back to normal.

But is this the real key to resolving the problem? Ideally and technically, yes.

Since the oil price increases had prompted the rise of other items’ prices as well, the lowering of the former should also bring down the prices of other commodities. But you see, this doesn’t happen even if the fuel prices are brought low.

Two obstacles hinder this thing from happening. First, oil prices in the country are dictated by the price of crude oil from oil-producing countries, and our government has no control over it. Second, even if the prices of oil are brought low, the prices of commodities that had gone up never go down anymore.

Take for example the fares in passenger vehicles, and the costs of fish and other marine products in the markets.

This is what the government should monitor and regulate, with necessary penalties for violators.